PIETER HUGO, CORPOREALITY

CORPOREALITY

Pieter Hugo

January 30th – April 25th, 2015

“Auch wenn es sich so anfühlt, als würde ich es schon seit jeher tun, bin ich immer noch schüchtern. Es ist einfacher, einen Fremden zu verprellen, als ihn kennenzulernen. Man muss zuerst erklären, wer man ist und welche Absichten man hat, und dann das unvermeidliche WARUM? beantworten. Dann der Akt der Überzeugung, um zu einer Übereinkunft zu gelangen. Das Gegenüber muss bereit sein, etwas zu geben. Ich möchte ihm nicht das Gefühl vermitteln, dass das Bild nur durch mein Handeln entstanden ist. Dafür braucht es – und darauf hoffe ich – einen Moment freiwilliger Verletzlichkeit.” – Pieter Hugo

Was heißt es heute, in Städten zu leben? Um diese Frage kreist das fotografische Werk von Pieter Hugo (*1976). Der südafrikanische Fotokünstler, der schon mit Anfang 20 – damals noch als Bildjournalist für u.a. die New York Times tätig – durch ganz Afrika reiste, erfasst vor allem die körperliche Präsenz von Menschen in ihren jeweiligen, oftmals von Dissonanzen geprägten Kulturen. Seine eindringlichen Porträts formieren sich zu einem sozialen Tableau, das die aktuelle und radikal kritische Lebenswirklichkeit nicht nur in afrikanischen Großstädten abbildet. In der ersten Einzelausstellung von Pieter Hugo in Deutschland zeigt | PRISKA PASQUER Werke aus seinen wichtigsten Serien, darunter „The Hyena and Other Men“ (2007), “Permanent Error” (2009-2010) und “There Is A Place in Hell for Me and My Friends” (2011-2012).

„Südafrika ist so ein zerbrochener, schizophrener, verwundeter und problematischer Ort,“ sagt Pieter Hugo. Wie kann man dort leben? Er empfinde sich als ein Stück „koloniales Treibholz“. Es ist wohl dieses Bewusstsein, das ihm die Augen öffnet für die Widersprüche und Dissonanzen, für die Reibungszonen und Spannungsfelder innerhalb der (süd-)afrikanischen Gesellschaft. In seiner 2005-2007 entstandenen „The Hyena Men Series“ hat Pieter Hugo das Drama der postkolonialen Gesellschaft erstmals exemplarisch erfasst. In Nigeria fand er eine Gruppe junger Männer, die mit Hyänen, Pavianen und Schlangen leben. Einer Tradition folgend, ziehen sie mit ihren Tieren als Schausteller umher und verkaufen traditionelle Medizin. Ihre Auftritte gelten als Sensation und finden ein begeistertes Publikum. In seinen vor der Kulisse konturloser Shantytowns entstandenen Aufnahmen konzentriert sich Pieter Hugo auf das Verhältnis der Männer zu ihren Tieren. Die klar komponierten Fotografien sind verstörende Sinnbilder für die extreme Spannung zwischen Natur und Kultur, zwischen Mensch und Tier, Tradition und Moderne, Stadt und Wildnis, die das Leben in den Städten der Subsahara heute prägt.

Müllkippe Europas – auch das ist Afrika. So landet ein Großteil der im Westen ausrangierten Handys, Computer und Laptops in Ghana, wo sich der containerweise herbeigeschaffte Computerschrott zu riesigen Halden türmt. Die Deponien liegen nicht einfach brach, sondern sind zu einem prekären Arbeitsraum für Tausende von Menschen geworden, die hier als Metallsammler ihr Auskommen suchen. Zusammen mit ihren Kühen leben sie auf den hochgiftigen, schwelenden Abfallbergen und versuchen, durch Verbrennen der Geräte an verwertbare Metalle zu kommen. Pieter Hugo hat auf einer Mülldeponie am Stadtrand von Accra apokalyptische Szenarien fotografiert – bedrohliche Visionen einer Endzeit, in der Informationszeitalter und Steinzeit aufeinanderprallen und sich gegenseitig auszulöschen scheinen. In der Ausstellung wird die auf der Serie „Permanent Error” (2009-2010) basierende Videoinstallation gezeigt.

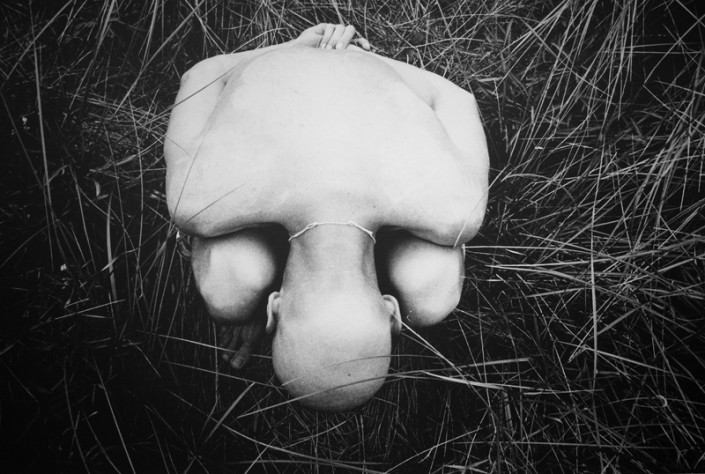

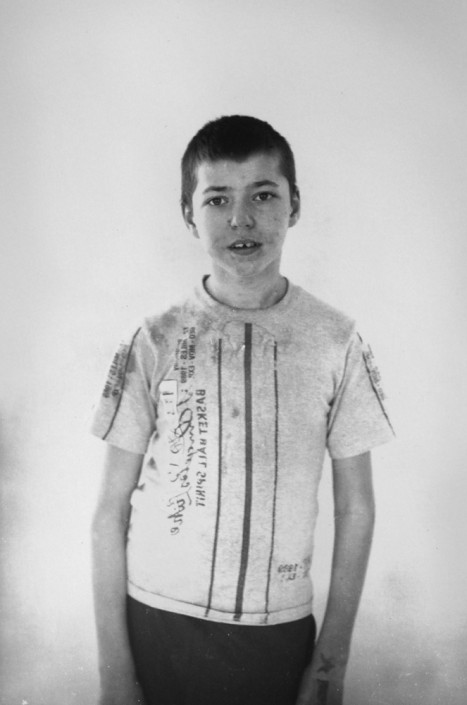

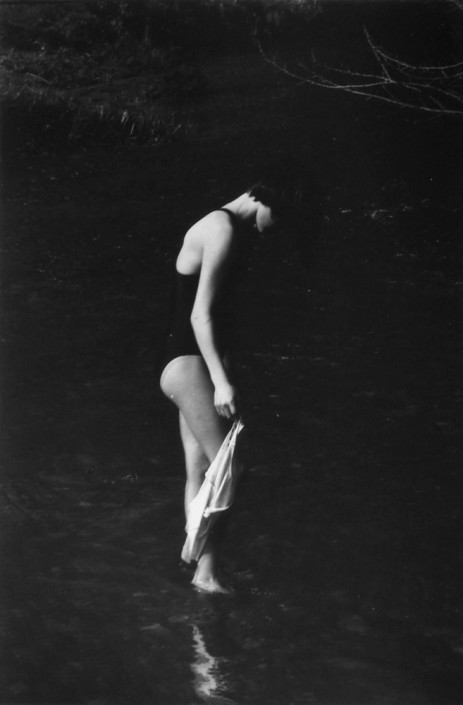

Zwischen 2006 und 2013 arbeitete Pieter Hugo an einem Projekt, das er „Kin“ (Sippe) nannte. Darin geht es um Heimat, Nähe, Identifikation und Zugehörigkeitsgefühl – etwas, das er in Südafrika von jeher als kritisch und konfliktgeladen erlebt hat: Wie kann man leben in diesem Land, das sein koloniales Erbe noch lange nicht hinter sich gelassen hat und geprägt ist von Rassismus und einer immer größer werdenden Kluft zwischen Arm und Reich? Hugo fotografierte zu Hause, in Townships und an historischen Plätzen, machte Porträts seiner schwangeren Frau, von Hausangestellten und Obdachlosen. Die ruhigen und klar komponierten Aufnahmen zeigen Schönheit und Hässliches, Reichtum und Armut, Privates und Öffentliches, Historisches und Aktuelles. Weder idealisierend noch dramatisierend entwerfen sie ein Porträt der komplexen Gesellschaft im heutigen Südafrika.

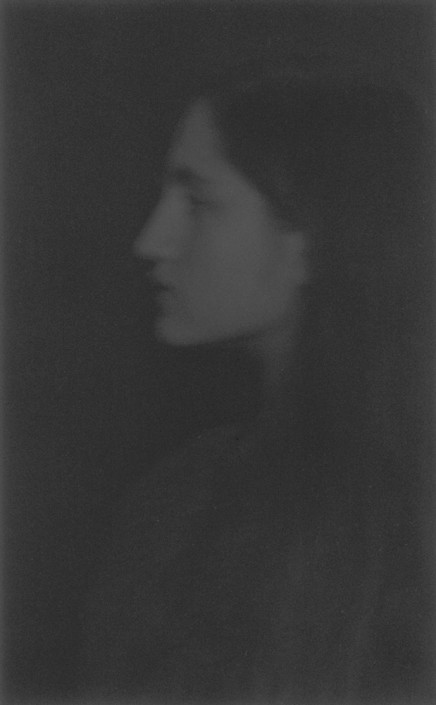

Denn die Einigkeit der so genannten Regenbogennation ist Wunschdenken. Auch zwanzig Jahre nach dem Ende der Apartheid sind Schwarz und Weiß in Südafrika noch lange nicht eins. In der 94 Platinum-Prints umfassenden Serie “There Is A Place in Hell for Me and My Friends” (2011-2012) beschäftigt sich Pieter Hugo mit den vermeintlichen Unterschieden der Hautfarben. Dafür hat er hat sich selber und südafrikanische Freunde porträtiert. Die in Nahaufnahme, zumeist als frontale Brustbilder aufgenommenen Farbfotografien wurden digital nachbearbeitet. Die Bildmanipulation, bei der die Farbkanäle in Grauwerte übersetzt wurden, betont die Pigmentierung der Haut und macht durch UV-Einstrahlung entstandene Hautschäden sowie kleine, direkt unter der Haut liegende Blutgefäße sichtbar. Das Ergebnis ist verblüffend: Auf diesen Fotografien sind alle Menschen farbig. Es gibt keine Unterschiede mehr zwischen „weißer“ und „schwarzer“ Haut, sondern nur noch eine Vielzahl individueller Tönungen. Die Porträts zeigen die kraftvolle Präsenz eines jeden Individuums und offenbaren zugleich die Verletzlichkeit aller Menschen, die Zartheit und Angreifbarkeit ihrer äußeren Hülle.

Mit seinen verschiedenen Bildserien hat Pieter Hugo in nur wenigen Jahren ein beeindruckendes Œuvre vorgelegt. Über die intensive Wahrnehmung der Körperlichkeit erfasst er in seinen Menschenbildern die Komplexität und Widersprüchlichkeit der Gesellschaft. Konstanten seines Werks sind Ernsthaftigkeit, Neutralität sowie ein grundsätzlicher Respekt vor seinem Gegenüber, dessen Würde stets gewahrt bleibt. Von diesem Ansatz her sind seine Arbeiten mit dem monumentalen Porträtwerk August Sanders vergleichbar, der mit seinem großangelegten Zyklus „Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts“ ein Zeitbild der Weimarer Republik geschaffen hat.

Im Jahre 1976 in Johannesburg geboren, lebt und arbeitet Pieter Hugo in Kapstadt.

Bislang wurde seine Werke u.a. in folgenden wichtigen Museumsausstellungen gezeigt:

The Hague Museum of Photography, Musée de l’Elysée in Lausanne, Ludwig Museum in Budapest, Fotografiska in Stockholm, MAXXI in Rom und im Institute of Modern Art Brisbane. Pieter Hugo hat an vielen wichtigen Gruppenausstellungen teilgenommen, beispielsweise in der Tate Modern, im Folkwang Musem, in der Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian und auf der São Paulo Biennale. Seine Werke in folgenden Sammlungenvertreten: Museum of Modern Art, V&A Museum, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, J Paul Getty Museum, Walther Collection, Deutsche Börse Group, Folkwang Museum und Huis Marseille. Im Jahr 2008 erhielt Pieter Hugo den Discovery Award beim Rencontres d’Arles Festival und den KLM Paul Huf Award und 2011 den Seydou Keita Award auf der Rencontres de Bamako African

Photography Biennale. 2012 wurde er für den Deutschen Börse Photography Prize nominiert.

“Even though it feels like I’ve been doing it forever, I am still daunted. It is easier to alienate a stranger than it is to get to know a stranger. You first have to explain who you are and what your intentions are, and then answer to the inevitable WHY? Then the act of persuasion, coming to an agreement. The subject has to be willing to give something. I don’t want it to feel like the image was taken with me only taking. It needs and I hope for a moment of voluntary vulnerability.” – Pieter Hugo on Portraiture

What does it mean to live in cities today? This question is central to the photographic works of Pieter Hugo (*1976). The South African photo artist, who travelled through Africa while only in his early twenties – then still as a photo journalist for the New York Times and other publications – captures above all the corporeal presence of people in their respective, often conflict-ridden cultures. His urgent portraits come together to form a social tableau that depicts the current and radically critical realities of life, not only in African cities. In the first ever exhibition in Germany to be devoted entirely to the works of Pieter Hugo, | PRISKA PASQUER will be showcasing works from his most important series, including “The Hyena and Other Men” (2007), “Permanent Error” (2009-2010) and “There Is A Place in Hell for Me and My Friends” (2011-2012).

“South Africa is a fractured, schizophrenic, wounded and troubled place”, says Pieter Hugo. How can one live there? He feels like a “piece of colonial driftwood”, which is arguably what opens his eyes to the contradictions and conflicts, for the areas of friction and tension that exist within (South) African society. In “The Hyena Men Series” (2005-2007), Pieter Hugo exemplified the innate drama of post-colonial society for the first time. In Nigeria, he found a group of young men living with hyenas, baboons and snakes. Following a tradition, they travel around as actors with their animals and sell traditional medicine. Their performances create a sensation and enthral audiences. In his shots, taken against the backdrop of contourless shanty towns, Pieter Hugo focuses on the men’s relationship with their animals. The clearly composed photographs are unsettling images that symbolise the extreme tension between nature and culture, between humans and animals, tradition and modernity, city and wilderness that characterises urban sub-Saharan life today.

Africa also serves as a rubbish dump for Europe. Many of the mobile phones, computers and laptops discarded in the West end up in Ghana, where container-loads of computer scrap are piled up high. The deposits are not simply left idle, but rather serve as a precarious working environment for thousands of people who earn a living collecting metal here. Together with their cows, they live on the highly toxic, smouldering mountains of waste, burning appliances in search of reusable metals. Pieter Hugo photographed apocalyptic scenarios on a rubbish dump on the outskirts of Accra – ominous visions of an endgame in which the Information Age and the Stone Age collide and appear to eliminate one another. The exhibition also features the video installation based on the series “Permanent Error” (2009-2010).

Between 2006 and 2013, Pieter Hugo worked on a project that he called “Kin”. This deals with home, proximity, identification and a sense of belonging – something that, in South Africa, he has always experienced as being critical and riddled with conflict: How can one live in this country, which only shed its colonial heritage relatively recently, and which is plagued by racism and a growing chasm between rich and poor? Hugo shot photos at home, in townships and at historical sites, taking portraits of his pregnant wife, of domestic servants and of homeless people. The calm and clearly composed shots show beauty and ugliness, wealth and poverty, private and public, historical and topical. Without either idealising or dramatizing the subject matter, they paint a portrait of the complex society in South Africa today.

This is because any notion of harmony in the “Rainbow Nation” is wishful thinking. Even twenty years after the end of apartheid, black and white South Africans are still very much divided. In the series of 94 platinum prints “There’s A Place in Hell for Me and My Friends” (2011-2012), Pieter Hugo explores the supposed differences between skin colours. To do so, he took portraits of himself and South African friends. The close-ups, generally in the form of frontal head and shoulder portraits, were digitally processed afterwards. The image manipulation, whereby the colour channels were translated into grey tones, emphasise the pigmentation of the skin, using UV irradiation to render visible skin damage and small blood vessels directly beneath the skin. The results are quite astounding: on these photographs, all people are coloured. There is no longer a difference between “white” and “black” skin, but rather a variety of individual shades. The portraits show the powerful presence of each individual and, at the same time, the fragility of all people and the softness and utter vulnerability of their outer shell.

With his various photo series, Pieter Hugo has put together an impressive body of work in the space of just a few years. Through this intense perception of corporeality, he captures the complexity and inconsistency of society. Constants in his work include seriousness, neutrality and an underlying respect for his protagonists, whose dignity always remains intact. In this regard, his works are comparable with the monumental portrait works of August Sanders, who created a contemporary picture of the Weimar Republic with his large-scale cycle “Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts” (People of the 20th Century).

Pieter Hugo (born 1976 in Johannesburg) is a photographic artist living in Cape Town. Major museum solo exhibitions have taken place at The Hague Museum of Photography, Musée de l’Elysée in Lausanne, Ludwig Museum in Budapest, Fotografiska in Stockholm, MAXXI in Rome and the Institute of Modern Art Brisbane, among others. Hugo has participated in numerous group exhibitions at institutions including Tate Modern, the Folkwang Museum, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, and the São Paulo Bienal. His work is represented in prominent public and private collections, among them the Museum of Modern Art, V&A Museum, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, J Paul Getty Museum, Walther Collection, Deutsche Börse Group, Folkwang Museum and Huis Marseille. Hugo received the Discovery Award at the Rencontres d’Arles Festival and the KLM Paul Huf Award in 2008, the Seydou Keita Award at the Rencontres de Bamako African Photography Biennial in 2011, and was shortlisted for the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize 2012.