FUTURISM

FUTURISM

“A racing car, whose body is decorated by giant pipes, a screaming car, is more beautiful than the Nike of Samothrake…”

With this aesthetic credo, the Futurists celebrated the birth of a new movement, which established for the first time as central measure the beauty and dynamism of technology in an industrial world.

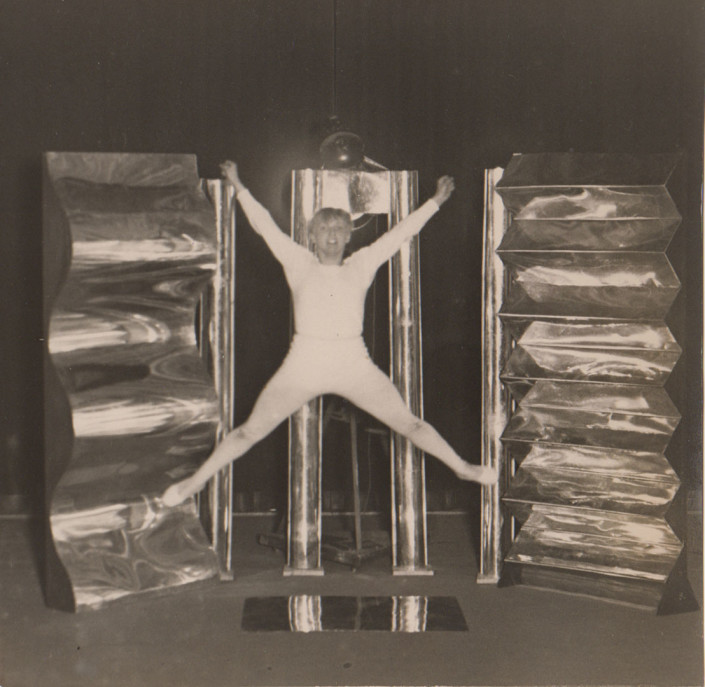

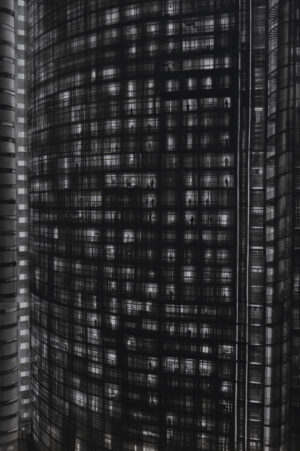

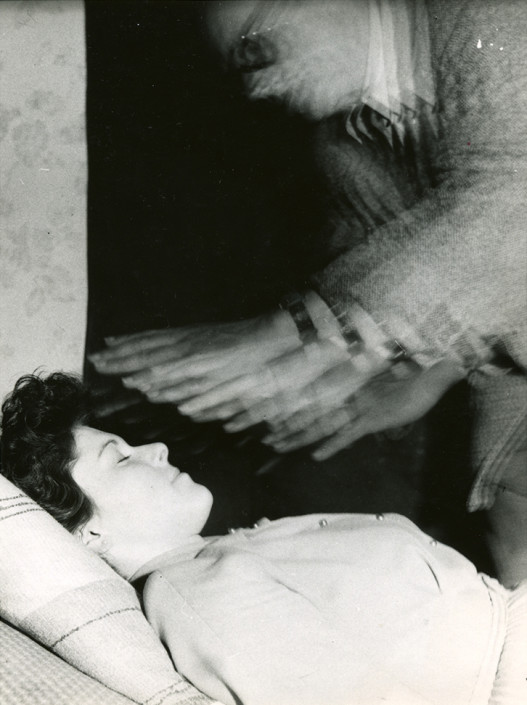

Originating from poetry and painting, for the duration of their thirty-year existence the Futurists embraced all spheres of art production: sculpture, theater, dance, cinema, music, design and architecture. Photography found, after an initial rejection, a manifold application within the movement: as artistic medium under the catchword “Photodynamism” with the goal of representing movement – in the form of montages and collages, self-portraits of the protagonists and, not lastly, to document the multiple activities of the Futurists themselves.

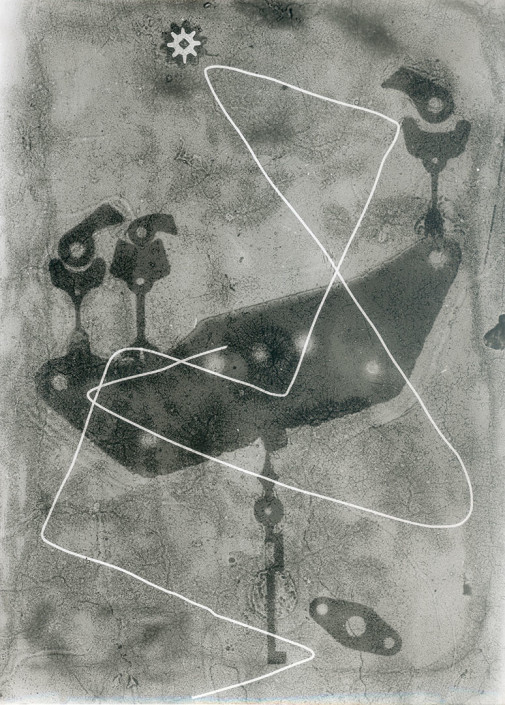

Presented here are photographs featuring collage/montage, portraiture and important documentary photographs portraying the Futurist movement itself. Among the montages and collages, alongside works of Gino Soggetti and Fillia, the series of compositions and self-portraits of the artist Adele Gloria deserve special attention.

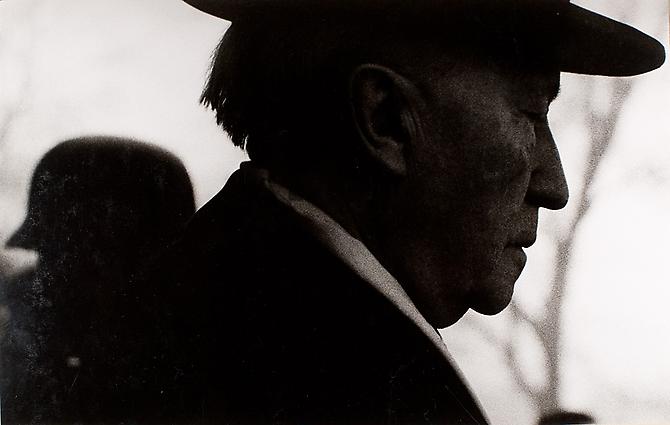

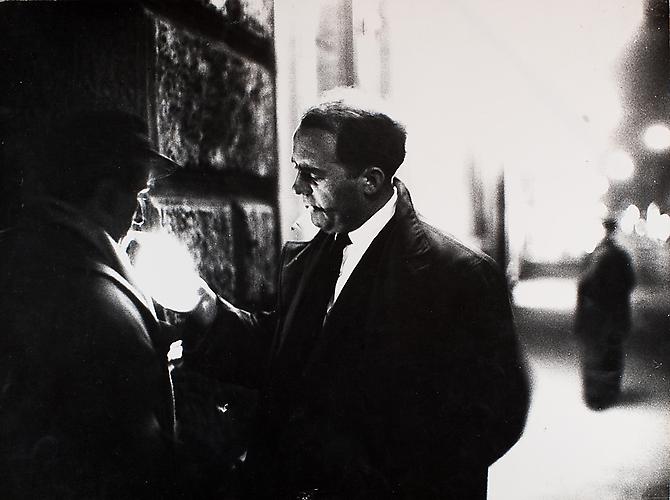

A great number of the Futurists made use of the photographic portrait for purposes of self-propaganda, whereby the works range from those manipulated in the darkroom to, ironically enough, the straight studio portrait in bourgeois costume.

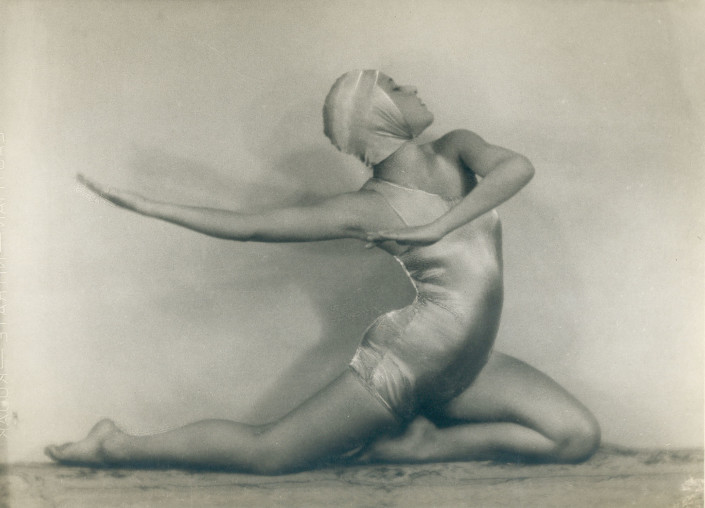

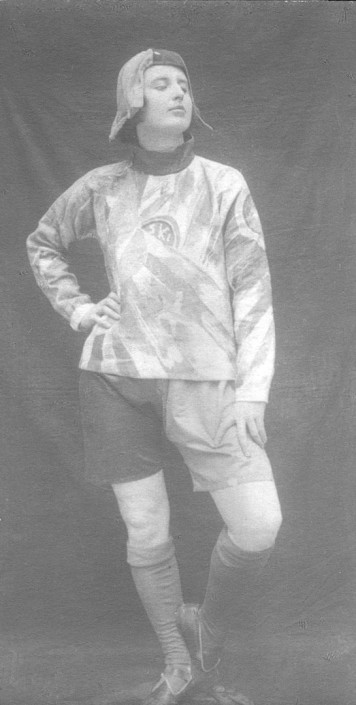

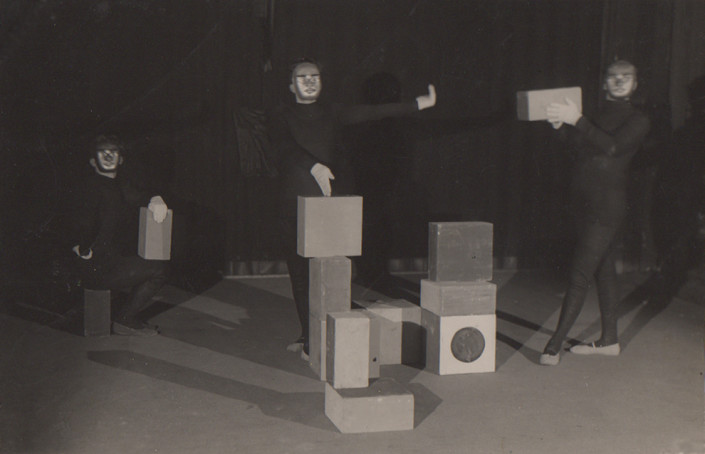

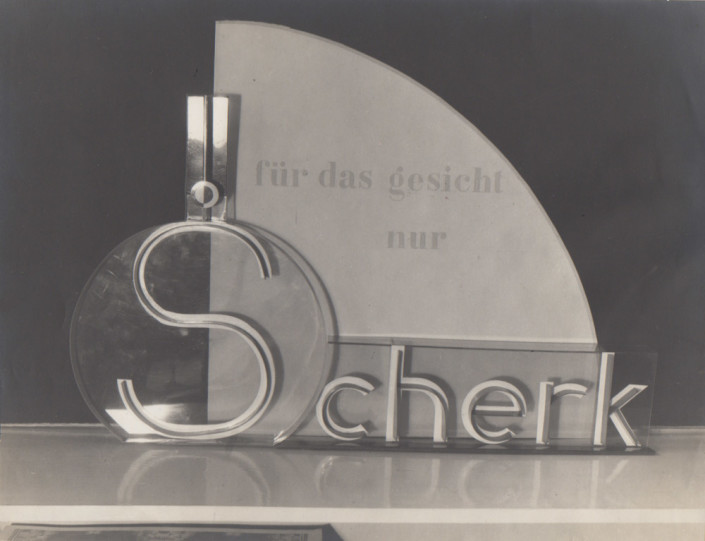

In order to document their activities and propagate the movement in the public print media, photography proved the ideal medium. Photographs originated – made by the Futurists themselves or by professional photography studios – of dance performances, stage design, costumes, architectural models and sculptural works.

The utopian, artistic concept of the Futurists was designed to destroy bourgeois tradition, whereby the basic premise included the postulate of dynamism in a technological society and the simultaneity of perception. Their revolutionary concept was realized especially on the border between literature and painting under the motto “Parole in Liberta” (word in freedom). With their free typographic constructions they destroyed the force of classical order and created scriptural pictures with dancing words and sounds which could be construed “simultaneously” by the reader.

In general, the Futurists accompanied and defined all spheres of their art production with manifests, books and newspapers. The multi-lingual written documents of the Futurists point to the internationality of their intent and their close relationships to the avant-garde movements in Europe. Above all, Dadaism and Surrealism embraced the artistic inventions of the Futurists, such as montage and sound poems.

„Ein Rennwagen, dessen Karosserie große Rohre schmücken, ein aufheulendes Auto, ist schöner als die Nike von Samothrake” mit diesem ästhetischen Credo feierten 1909 die Futuristen die Geburt einer neuen Bewegung, die erstmals die Schönheit und Dynamik der Technik einer industrialisierten Welt als zentralen Maßstab setzte.

Ausgehend von der Poesie und Malerei begannen die Futuristen während ihrer rund 30jährigen Existenz auf alle Bereiche der Kunstproduktion zuzugreifen: Skulptur, Theater, Tanz, Kino, Musik, Design und Architektur. Die Fotografie fand nach anfänglicher Ablehnung vielfältigen Einsatz innerhalb der Bewegung: als künstlerisches Medium unter dem Schlagwort des „Fotodynamismus“ mit dem Ziel der Darstellung von Bewegung; in Form von Montagen und Collagen; zur Selbstdarstellung der Protagonisten und nicht zuletzt zur Dokumentation der vielfältigen Aktivitäten der Futuristen.

In der Ausstellung werden rund 70 Fotografien mit den Schwerpunkten Collage/Montage, Portrait und Dokumentarfotografie gezeigt. Bei den Montagen und Collagen ist insbesondere, neben Arbeiten von Gino Soggetti und Fillia, eine Serie von Kompositionen und Selbstporträts der Künstlerin Adele Gloria hervorzuheben.

Etliche der Futuristen nutzten das fotografische Porträt zur Selbstpropaganda, wobei die Bandbreite von in Labor verfremdeten Arbeiten bis hin zu Porträts im „bürgerlichen” Habitus reicht (z. B. Marasco, Marinetti u. Pannaggi).

Um ihre Aktivitäten zu dokumentieren und in den Printmedien der Zeit zu propagieren, stellte die Fotografie das ideale Medium dar. Es entstanden Aufnahmen – durch die Futuristen selbst oder von professionellen Fotografen – von Tanzperformances, Bühnenbildentwürfen, Kostümen, Architekturmodellen und Werken der bildenden Kunst (Depero, Kertéz, Prampolini u.a.).

Das utopische, künstlerische Konzept der Futuristen hatte sich die Zerstörung der bürgerlichen Traditionen auf die Fahnen geschrieben, wobei zu den Grundprämissen das Postulat der Dynamik einer technoiden Gesellschaft und der Simultanität der Wahrnehmung gehörte. Ihren revolutionären Ansatz verwirklichten die Futuristen besonders auf der Grenze zwischen Literatur und Malerei unter dem Schlagwort „Parole in Libertà” (Worte in Freiheit). Sie setzten mit ihrer freien typografischen Gestaltung die klassische Ordnung der Texte außer Kraft und schufen Schriftbilder mit tanzenden Worten und Lauten, die vom Leser „simultan” erfasst werden sollten.

Beispiele der „Parole in Libertà” werden in der Ausstellung sowohl in Form von Zeichnungen als auch in Publikationen wie z. B. die zentrale Schrift „Le mots en liberté futuristes” von F. T. Marinetti (1919) ausgestellt. Generell haben die Futuristen alle Bereiche ihrer Kunstproduktion in Manifesten, Büchern und Zeitschriften begleitet und definiert, wovon eine Auswahl von den Anfängen der Futuristen bis in die 1930er Jahre gezeigt wird (unter anderem das eingangs zitierte Gründungsmanifest der Futuristen von F. T. Marinetti von 1909).

Die mehrsprachigen Schriften der Futuristen verweisen auf ihre internationale Ausrichtung und ihre engen Beziehungen zu den Avantgardebewegungen in Europa. Vor allem Dadaismus und Surrealismus griffen künstlerischen Inventionen wie die Montage und das Lautgedicht der Futuristen auf. Zugleich trug die futuristische Bewegung seit ihrem ersten Manifest einen starken totalitären Impuls in sich. Patriotismus und Nationalismus führten seit Beginn der 20er Jahre zu einer engen Beziehung zu Benito Mussolini und seiner faschistischen Bewegung, was sich vor allem in späteren Arbeiten niederschlägt.