ELFRIEDE STEGEMEYER

Elfriede Stegemeyer’s (1908-1988)

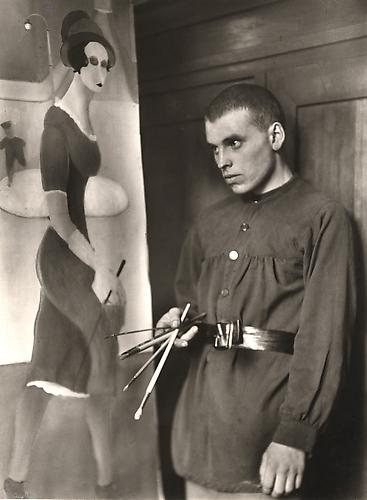

Elfriede Stegemeyer’s beginnings in photography and her development of an independent photographic oeuvre were predominantly of an autodidactic nature. From an upper class background (Kaffee HAG), she studied at the Staatliche Kunstschule art school in Berlin, and in 1932 followed the painter Otto Coenen to Cologne, where she lived until 1939. Here, she attended the photography class held at the Cologne Werkschulen. Her only fellow student in the class was Raoul Ubac. Through Coenen, Elfriede Stegemeyer was introduced into the circle of the Kölner Progressive (Cologne Progressives) centred around Franz W. Seiwert and Heinrich Hoerle. She became a member of the Cologne resistance group Rote Kämpfer (Red Fighters).

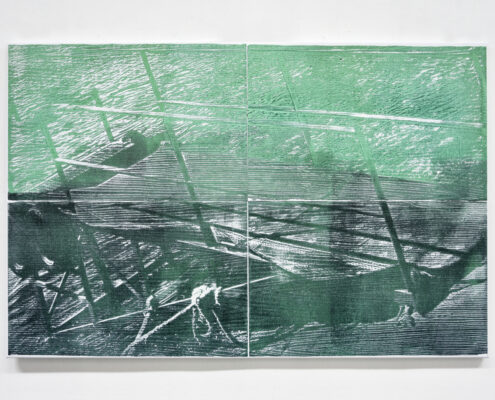

During this period, Elfriede Stegemeyer experimented extensively with photography and, influenced by the photographic avant-garde of the Weimar Republic, she explored the boundaries and possibilities of the medium. Her work was principally based on the world of everyday objects, which she used as material for her photograms, photomontages, multiple exposures etc. She predominantly employed glass objects, especially drinking glasses for her studies, intended for a (never published) book Die Schule des Sehens (The School of Seeing). She arranged objects in unusual perspectives and dynamic arrangements, creating effects of light and shade. In addition to the still lifes and experimental work, she also photographed Cologne and its environs; a series of shop window mannequins are particularly noteworthy.

In 1935 she travelled with Coenen to Paris. Here, a close relationship developed between her and Raoul Hausmann, with whom she stayed for several months at Ibiza. On the island, she photographed architecture and landscapes. Later, during journeys to eastern Europe, she documented the everyday life of the population there until 1938. Her return to Berlin in 1939 and the outbreak of war in 1939, marked the end of her independent artistic work. In 1941, she was arrested by the Gestapo for high treason, but was released again. Sadly, a large part of her oeuvre was destroyed during a bombing raid in 1943. After the war, she began a second artistic career under the name of elde steeg.

Elride Stegemeyer (1908-1988)

Mit Elfriede Stegemeyer wird eine Künstlerin vorgestellt, die in einer politisch ausgesprochen schwierigen Zeit einen eigenen künstlerischen Weg gegangen ist. In der Zeit der Unterdrückung und Verfolgung der künstlerischen Avantgarde entwickelte Elfriede Stegemeyer einen offenen, experimentellen Umgang mit dem Medium Fotografie, der sie eine Sonderrolle in der deutschen Kunstgeschichte der 30er Jahre einnehmen lässt.

Der Weg in die Fotografie und zu ihrem künstlerischen Oeuvre war weitgehend autodidaktisch. Aus großbürgerlichem Hause (Kaffee HAG) stammend, studierte sie an der Staatliche Kunstschule in Berlin und folgte 1932 dem Maler Otto Coenen nach Köln, wo sie bis 1939 wohnte. Dort besuchte sie an den Kölner Werkschulen u. a. einen Fotokurs, einziger Mitstudent in dem Kurs war Raoul Ubac. Über Coenen fand sie Kontakt zu dem Kreis der Kölner Progressiven um Franz W. Seiwert und Heinrich Hoerle und sie wurde Mitglied in der Kölner Widerstandsgruppe der Roten Kämpfer.

In dieser Zeit experimentiere Elfriede Stegemeyer intensiv mit der Fotografie und in Anlehnung an die Fotoavantgarde der Weimarer Republik erkundete sie die Grenzen und Möglichkeiten des Mediums. Ausgangspunkt ihrer Arbeit war vor allem die Objektwelt der alltäglichen Dinge, die Sie als Vorlagen für Fotogramme, Fotomontagen, Mehrfachbelichtungen, etc. eingesetzt hat. Vor allem gläserne Objekte und besonders Trinkgläser dienten als Material für ihre Studien, die für ihr unpubliziertes Buch „Die Schule des Sehens“ gedacht waren. Sie arrangierte die Dinge in ungewohnten Perspektiven, dynamischen Kompositionen und unter dem effektvollen Einsatz von Licht und Schatten. Neben den Stillleben und Experimenten entstanden auf Aufnahmen in Köln und Umgebung, wobei besonders eine Serie von Schaufensterpuppen hervorzuheben ist.

1935 reiste Elfriede Stegemeyer mit Otto Coenen nach Paris wo sich in kurzer Zeit eine enge Beziehung zu Raoul Hausmann entwickelt. Raoul Hausmann war im März 1933 nach Ibiza gereist und dort als Emigrant geblieben. Stegemeyer’s Begegnung mit Raoul Hausmann führte zur Trennung von ihrem Lebensgefährten Otto Coenen. Zunächst wollten Raoul Hausmann und Elfriede Stegemeyer heiraten, doch dafür war es notwendig, dass Hausmann sich von seiner bisherigen Frau Heta in Prag scheiden ließ. Gemeinsam gingen Hausmann und Stegemeyer auf die für beide gefährlichen Reise nach Prag. Bei einem Zwischenaufenthalt in Berlin bei der Malerin Maragrete Kubicka kam es allerdings zu einem Streit und das Paar trennte sich.

Dennoch nahm Stegemeyer im August des selben Jahres eine Einladung von Hete und Raoul Hausmann nach Ibiza an. Raoul Hausmann betrieb auf Ibiza intensive ethnologische Studien sowohl in Hinsicht auf die Sozialgeschichte als auch auf die natürlichen Gegebenheiten. Auch Elfriede Stegemeyer hatte Interesse an diesem Fachgebiet, welches durch Hausman wohl noch verstärkt worden ist. Gemeinsam haben Hausmann und Stegemeyer auf Ibiza vor allem Architektur und Landschaft fotografiert. Für Elfriede Stegemeyer bot vor allem die traditionelle Architektur mit ihren kubischen Formen eine vorzügliche Vorlage für ihre neusachliche, konstruktivistische Bildauffassung.

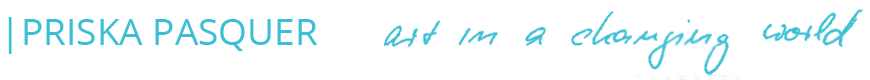

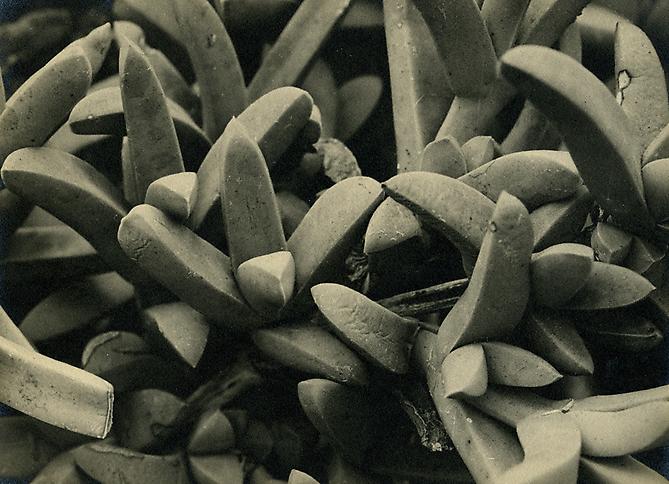

Sie konzentrierte sich in ihrem Arbeiten vor allem auf Formen, Texturen und Schichtungen und verzichtet dabei auf jegliches erzählende Detail. Neben der Architektur sind Kakteen und Olivenbäume wichtige Motive als Ausdruck von Kraftstömungen und natürlicher Formenvielfalt. Der Olivenbaum bleibt in den nächsten Jahrzehnten ein Motiv ihrer künstlerischen Arbeit und findet sich auch in späteren Zeichnungen wieder. Von Elfriede Stegemeyer’s Aufenthalt in Ibiza sind sowohl eine Reihe von Einzelaufnahmen und ein handgearbeitetes Album mit 18 Fotografien erhalten. Das Fotoalbum wurde 2008 im Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia im Rahmen der Ausstellung „A. C. Actividad Contemporánea. La revista del GATEPAC (AC, The Magazine Produced by GATEPAC)“ gezeigt.

Ende 1935 führten Auseinandersetzungen mit Raoul Hausmann zur Rückkehr der Künstlerin nach Deutschland. Raoul Hausmann verließ Ibiza 1936 unter dem Eindruck des Vormarsches der Franko Truppen. In den Jahren von 1949 bis 1954 hatten beide Künstler erneut brieflichen Kontakt. In der zweiten Hälfte der 1930er Jahre dokumentierte Elfriede Stegemeyer auf Reisen in Osteuropa das Alltagleben der Bevölkerung. Mit ihrem Umzug 1939 nach Berlin und dem Kriegsausbruch endete ihre künstlerische Arbeit. 1941 wurde sie wegen Hochverrats von der Gestapo verhaftet, musste jedoch aus Mangel an Beweisen wieder freigelassen werden.

Der größte Teil ihres Oeuvres wurde 1943 bei einem Bombenangriff zerstört. In der Nachkriegszeit begann Elfriede Stegemeyer eine zweite künstlerische Karriere unter dem Namen elde steeg.

Ein Überblick über das fotografischen Werk wurde 1999 vom Kunstverein Bremen publiziert: „Elfriede Stegemeyer. Fotografien“. Die Galerie Priska Pasquer hat die Fotografien in einer Einzelausstellung 2002 vorgestellt. Dem Leben und Werk der Künstlerin widmeten 2010 die Kunstsammlungen Böttcherstraße, Paula Moderson-Becker Museum, Bremen, unter dem Titel „Elfriede Stegemeyer – elde steeg. Doppelleben einer Avantgardistin“ eine Ausstellung mit Katalog.

ANNELISE KRETSCHMER

/in Europe /by admin1903-1987

The photographic work of Annelise Kretschmer (1903-1987) spans a period of time over five decades, beginning in the middle of the 1920s. After attending the School of Decorative Arts in Munich, where she studied drawing and bookbinding, she first worked voluntarily in the portrait studio of E. Kaenel in Essen (1922-1924), and then as master disciple of Franz Fiedler in Dresden (1924-1928).

Except for small series with images from trips to Paris and Hiddensee, Annelise Kretschmer concentrated on portraiture. She published her work regularly in publications like “Das Atelier” and, towards the end of the 1920s she opened in Dortmund her own portrait studio. In 1920 she participated in the legendary traveling exhibition “Film und Foto,” and in 1930 the exhibition “Das Lichtbild.” In 1928 she married the sculptor Sigmund Kretschmer. Through him her experience of contemporary art was deepened.

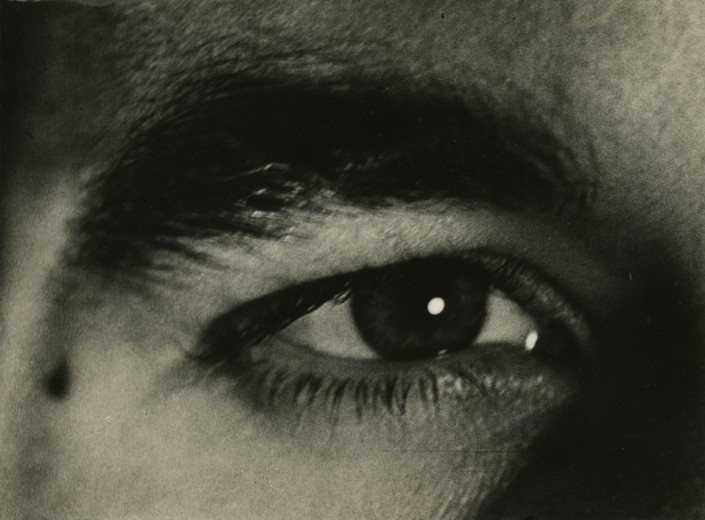

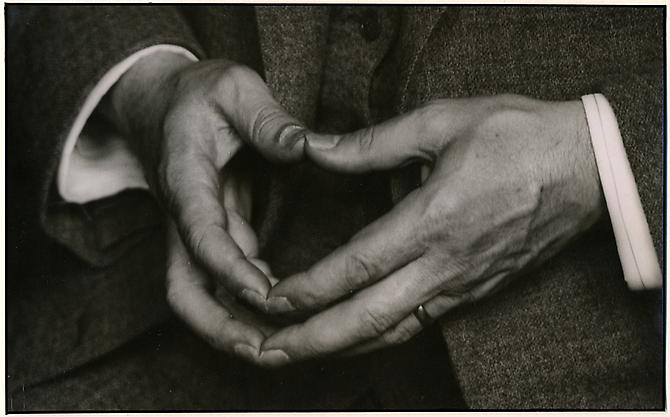

The early photographs of Annelise Kretschmer are to be seen in the context of “New Photography,” where she experimented with cropping and form, whereby in the sphere of portraiture it is always the personality of the subject, which is central. Two themes define the portrait photography of Annelise Kretschmer: images of her children in the 1930s, and the culturally active people and citizens from the area of her hometown Dortmund until the 1960s. The portraits of her children as well as her professional studio portraits are characterized by a great psychological intensity, which Annelise Kretschmer created through a concentration on mimic and gesture of the subject. At the same time, the environment is often diffused through strict cropping, the use of light and shadow and the clever choice of background, which appears in part almost painterly.

In 1943 the Kretschmer family moved to the region of Breisgau. In 1950 Anneliese Kretschmer reopened her studio, which had been destroyed in the war. In 1953 Sigmund Kretschmer died and from 1958 the artist worked together with her youngest daughter Christiane von Konigslow. Again, the “psychological portrait” formed the basis of her work, whereby her photographic style appears cooler and more objective. From the late 1950s it is mainly artists, like the sculptor Ewald matare or the photographer Albert Renger-Patzsch, who were photographed by Annelise Kretschmer.

ALBERT RENGER-PATZSCH

/in Europe /by admin1897-1966

Albert Renger-Patzsch was a leading German photographer associated with the New Objectivity in the 1920s and 1930s.

Renger-Patzsch was born in Würzburg and began making photographs by age twelve. After military service in the First World War he studied chemistry at Dresden Technical College. In the early 1920s he worked as a press photographer for the Chicago Tribune before becoming a freelancer and, in 1925, publishing a book, The choir stalls of Cappenberg. He had his first museum exhibition in 1927.

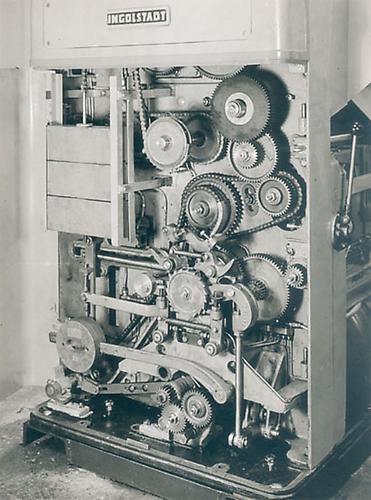

His best known photography book was published in 1928: „Die Welt ist schön“ (The World is Beautiful). It contains a collection of one hundred of his photographs in which natural forms, industrial subjects and mass-produced objects are presented with the clarity of scientific illustrations. In its sharply focused and matter-of-fact style his work exemplifies the esthetic of The New Objectivity that flourished in the arts in Germany during the Weimar Republic.

Renger-Patzsch’s photographs from the 1920s to 1950s excavate startling beauty and clarity from mundane sights of plants, buildings, and industrial machines.

“We still don’t appreciate the opportunity to capture the magic of material things. The structure of wood, stone and metal can be shown [in photography] with a perfection beyond the means of painting,” commented Renger-Patzsch on his work.

AUGUST SANDER

/in Europe /by admin1879-1964

German photographer. After seven years as a miner and a period of national service, he studied painting in Dresden from 1901 to 1902, which allowed him to approach photography artistically. He had developed an interest in photography through work in photographic firms in Berlin, Magdeburg, Halle and Dresden from 1898 to 1899. In 1901 he went to Linz, where he first worked in the Greif Studio, which he ran from 1902 with his partner Franz Stukenberg as the Studio Sander & Stukenberg, until he founded the Studio August Sander für Kunstphotographie und Malerei in 1904. He sold the studio in 1909 and returned to Cologne, where he ran the Studio Blumberg & Hermann, and in 1910 he founded his own studio in Lindenthal.

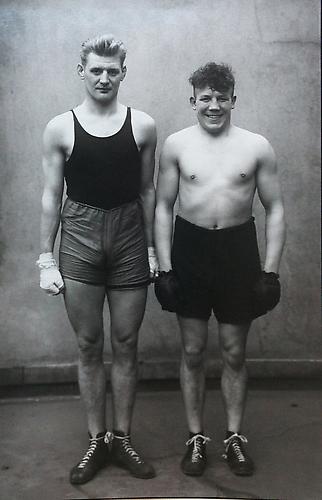

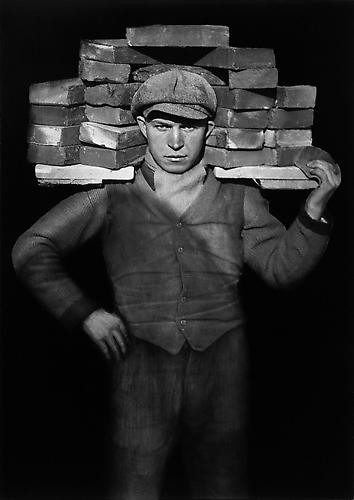

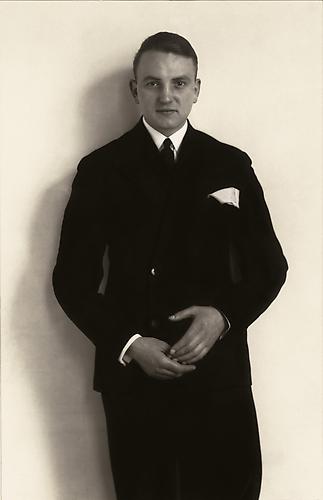

At this point Sander started his major project, Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts, with which he was involved until the 1950s. The theme for the project grew out of the portraits he made of Westerwald farmers, in whom he saw the archetypal contemporary man. Building on this, Sander developed a philosophy that placed man within a cyclic model of society. In these terms, the peasant class constituted the basis of society, hence his title for the series of 12 peasant portraits, Stamm-Mappe (see G. Sander, 1980, nos 1–12). The next group, of skilled workers, is the foundation of civic life, from lawyer to member of parliament, from soldier to banker. These are followed by intellectuals: artists, musicians and poets. The cycle closes with the Letzte Menschen, the insane, gypsies and beggars.

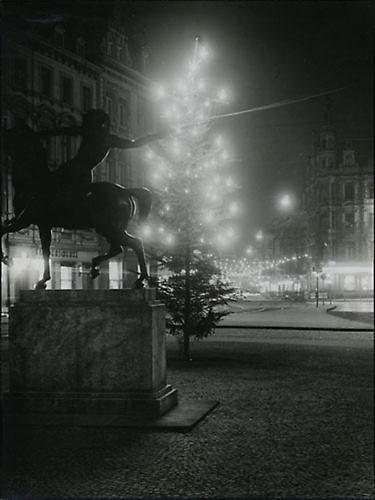

Although this cyclic model of society was anything but progressive, Sander came into conflict with the Nazis. The political activities of his son Erich were also held against him, and he had to interrupt work on this project between 1933 and 1939, when he devoted himself mainly to the themes of the Rhine countryside and the city of Cologne. The unusual quality of his portraiture is, above all, its systematic manner; this made the work a well-designed unity, not only in a sociological and philosophical sense, but also in photographic terms.

Sander’s portraits, whether half- or full-length, are always set in a simple environment. He gave a controlled and intentional hint at the origin and profession of the sitter through the background or through clothes, hairstyle and gesture. There is no doubt of the peasant origin of the Three Young Farmers in Sunday Dress, Westerwald (1913; Cologne, Mus. Ludwig) on their way to a dance, for example, despite their clothing. They are given away by the landscape background, their physiognomy, their clumsy shoes and the rough walking-sticks they are carrying. In contrast, Three Generations of a Farming Family (1912; see G. Sander, 1980, no. 12) shows clearly that the group had sat on their chairs especially for the photograph. In the same way, the Master Cobbler (c. 1924; see G. Sander, 1980, no. 97) is sitting almost demonstratively at his work table, looking into the camera. In the picture of the Publisher (c. 1923–4; see G. Sander, 1980, no. 280), posing nonchalantly with stick and newspaper, it is apparent that the subject’s relationship with the countryside behind him is not that of a farmer but of a walker.

Sander tried in all his works to incorporate this relationship of sitter to setting up to the last detail, with great confidence but at the same time with caution. Unfortunately he did not manage to publish his cycle during his lifetime. Through publication of Antlitz der Zeit and Deutschenspiegel in 1929, he could at least exhibit excerpts of his idea in book form. His son Gunther worked on Sander’s archive of more than 540 portraits and published them under the title that August had originally planned, Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts, in Munich in 1980.

After the demolition of his studio by bombing in 1944, when 40,000 negatives were destroyed, Sander retired to Kuchhausen in the Westerwald, where he carried on working under primitive conditions. His name was almost forgotten in Cologne, when L. Fritz Gruber, the organizer of the Photokina photographic exhibitions there, brought his photographs back to public attention by showing them at Photokina in 1951. He also convinced the city of Cologne to purchase for the Stadtmuseum the whole archive of views of the city, taken between 1935 and 1945, including the negatives. A publication titled Das alte Köln was to commemorate this purchase but was only completed posthumously in 1984. This part of Sander’s work also shows a systematic approach, giving proof on the one hand of his closeness to his home town and, on the other hand, of a very specific and unusual mode of perception. His series of landscape photographs of the Rhine area, taken between 1934 and 1939, is an analogous case, forgotten for a long time and only published in book form in 1975.

The reason for Sander’s international reputation as one of the most important German post-war photographers lies in his strict documentation of his view of Man. Although his selection of people was mainly influenced by personal meetings and was thus hardly representative in a demographic sense, his portraits remain highly accurate reflections of their time. His individual approach determined the nature of his work and guaranteed him an outstanding position in international documentary photography. In 1964 he received the culture prize of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Photographie, of which he had already been an honorary member since 1961. The great breakthrough in his public reputation, attested to by the retrospective mounted in 1969 by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, occurred only after his death.

Reinhold Misselbeck

From Grove Art Online

(Source: Oxford University Press)

OLIVER SIEBER

/in Europe /by admin*1966

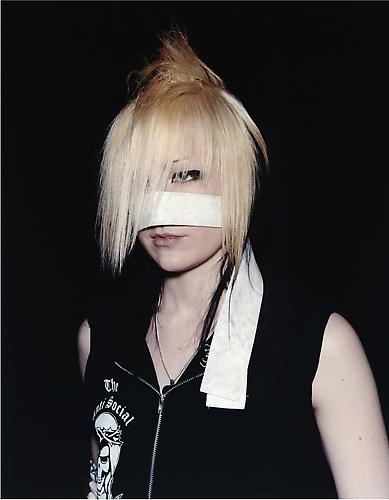

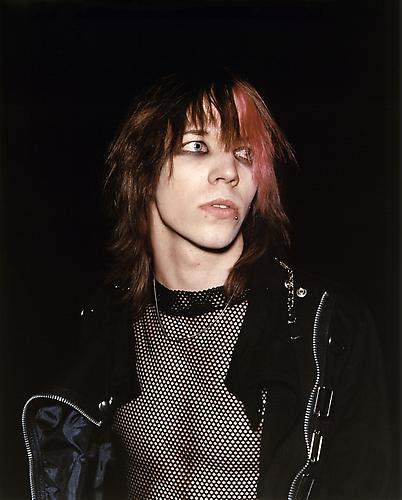

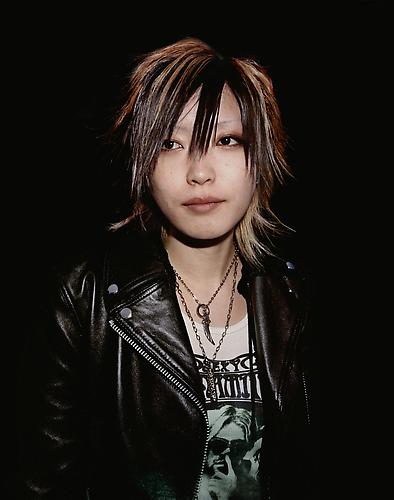

Youth and culture, music and society, identity and the search for individuality – these are the themes that define the works of photographer Oliver Sieber. Sieber seeks out clues in subcultural milieus, visiting clubs, concerts and illegal parties in Los Angeles, Toronto, Tokyo, Osaka, New York and small-town Germany. Here, he comes into contact with Punks, Visu’s, Psychobillies, Gothic Lolitas and Cosplayers – people who define their identity through codes, demonstrating membership of one group while distancing themselves from the mainstream.

With his Imaginary Club exhibition, Oliver Sieber has brought together the different protagonists from his series. In Imaginary Club, it is the heterogeneity and the nonconformist element shared by the personalities that captures the artist’s interest. “Imaginary Club represents a society in which I myself would love to live”, says Oliver Sieber. “A world where different forms of life co-exist effortlessly is something I find very appealing.”

Against a neutral background, the eyes of Sieber’s protagonists are trained on a point beyond the camera, conveying a defensive and melancholy mood. Although Sieber gets right up close to his models, they remain exactly as they are. As in many classical portraits, this distance is underlined by sculptural, static detail. In this way, Sieber’s protagonists become representatives of their respective peer groups, which in turn renders their style-code uniqueness interchangeable. The focus is then shifted onto the question as to whether or not an identity is possible.

The search for identity can therefore be seen as a journey – as an act of self-orientation that is continually determined by ourselves and those around us. On contemplating Oliver Sieber’s series of photographs, there is also a certain sense of longing that resonates at the same time – a sense of finding oneself, the past and the imaginary through the act of observing others.

Born in Duesseldorf in 1966. Studied photography in Bielefeld and Duesseldorf. 2005 Artist in Residence, Goethe Institut, Toronto. 2006 scholarship to Japan. Produced the “J_Subs” series and completed the “Character Thieves” series in Japan. 2009 German Photo Book Award (silver) for “Character Thieves”. Artist in Residence in Los Angeles as part of the “La Brea Matrix” project.

Published photo fanzine “Frau Boehm” from 1999 onwards together with artist Katja Stuke. In 2007, founded (with Stuke) the “Boehm/Kobayashi Publishing” label, under which many projects were produced.

Oliver Sieber’s works have been shown in numerous institutions, including: Photographers’ Gallery London; Photographische Sammlung SK/Stiftung Kultur Cologne; National Museum of Photography, Copenhagen; Photo España Festival, Madrid; Fotomuseum Winterthur; Fotohof Salzburg.

Selected Publications

Imaginary Club 2005-2012 Artist’s Book, 2012

Imaginary Club #2. Boehm/Kobayashi Publishing, 2010

J_Subs. Text: Christoph Schaden, Boehm/Kobayashi Publishing, 2009

Imaginary Club #1. Boehm/Kobayashi Publishing, 2008

Character Thieves. Text: Mariko Takeuchi (jap./ger.), Schaden-com feat. Boehm/Kobayashi Publishing, 2007

Die Blinden (The Blind). Text: Kerstin Stremmel, Schaden-com, Cologne, 2006

Deutsch/ Young Germany Photography

/ Oliver Sieber –

Uebungsräume – Skinsmodsteds. (ger./engl.)

Kruse Verlag, Hamburg, 2001