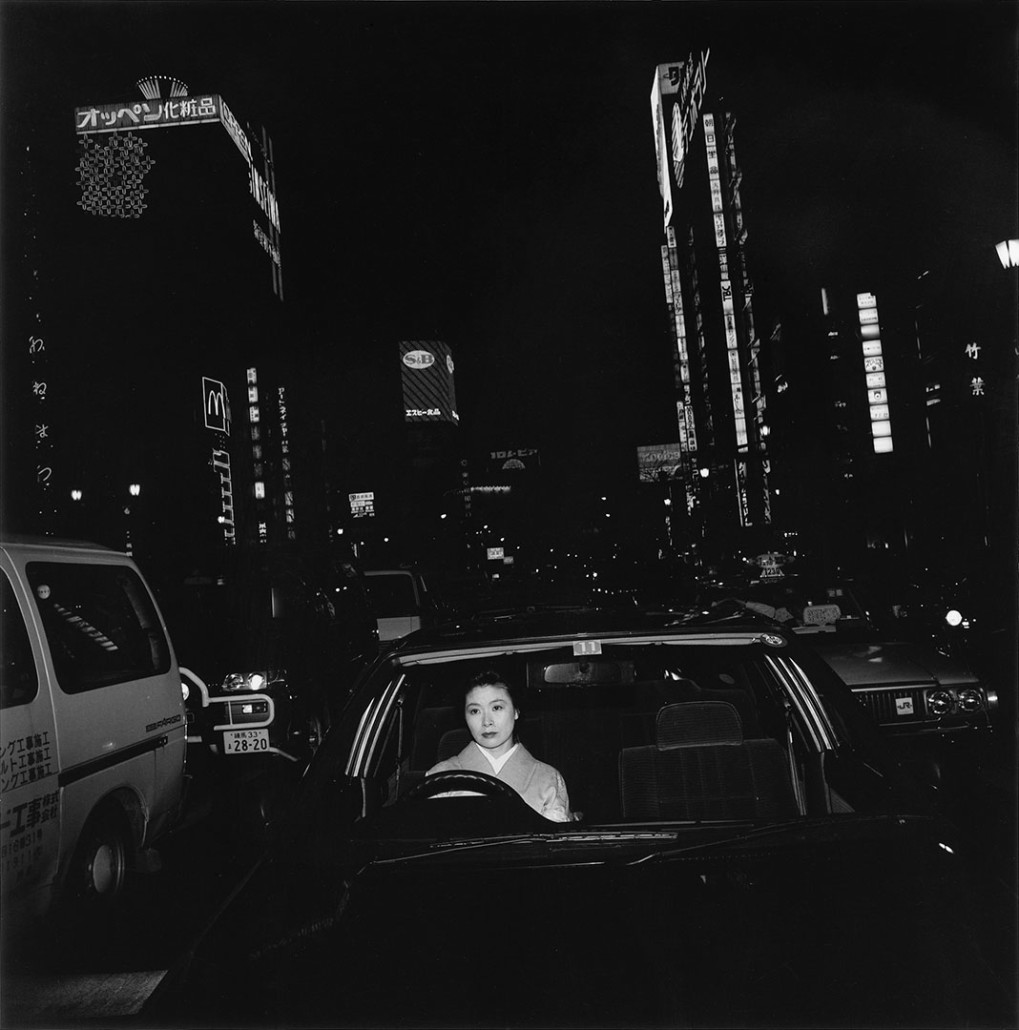

Issei Suda, a Master of Japanese Photography

Issei Suda, a Master of Japanese Photography.

Interview by Roland Angst with Ferdinand Brueggemann

Published in:

“Issei Suda – The Work of a Lifetime – Photographs 1968 – 2006“,

Only Photography, Berlin, 2011

Roland Angst (RA): Ferdinand, you were in Tôkyô for nearly two years – when was that? And what was behind your stay there?

Ferdinand Brueggemann (fb): In the late 1990s, I was there for 18 months as a research fellow at the German Institute for Japanese Studies. The title of the research project I was working on there was «The Influence of the German Avant- Garde on Japanese Photography of the 1920s and 1930s»; and then I was in Japan again in 2000 for several months to do research. Since then, I have been in Japan at regularly.

RA: Your work was already focused on photography due to your research project. How long did it take you to establish personal contacts to Japanese photographers and curators?

fb: That already happened during the first weeks of my stay. I had previously made two shorter visits to Japan, before I went there for my research, and got to know two curators – Hiromi Nakamura, from the Metropolitan Museum of Photography, and Masafumi Fukagawa, from the Kawasaki City Museum. They soon helped me to get in touch with a number of younger photographers. My daily routine during that period of doing research in Tôkyô involved working in the archives during the day and meeting photographers in the evening, there was always something new going on. At openings, exhibitions and award ceremonies, I had the opportunity to immerse myself in the Japanese photography scene.

RA: As far as I know, there still really isn’t a gallery scene in Japan like the one in the West. Where were you able to see the works of these photographers?

fb: The structure of the Japanese photography scene is completely different from what we are used to in the West. In Europe and in the USA, artists’ careers begin with gallery exhibitions, as a rule, and later progress to shows in museums, accompanied or followed by the first books on their work brought out by public institutions or private publishing companies. In Japan, on the other hand, the photographers first have a publicist or even produce the publications themselves. Another important step is for them to win one of the awards for young photographers. An exhibition at a recognized gallery, or even at a museum, often only comes after that. Yet, despite this fact, there are still countless photography exhibitions in Japan. I recently did some research and found out that on a single day in Tôkyô, exhibitions by roughly one hundred Japanese photographers were taking place. Many of these were, however, in what are known as “rental galleries”, spaces the artists rent for the equivalent of € 2,000 to € 3,000 per week in order to show their work. The one or the other of the Japanese photographers, with whom I had become acquainted, would always take me along to an exhibition opening or some similar event back then, because at that time absolutely no information on these exhibitions was available in English. It was only possible for foreigners to get to know the artists and their work, if another Japanese photographer provided you with the information or took you along with them.

RA: When and how did you first become acquainted with Suda’s work?

fb: It must have been while I was doing research in Tôkyô during the late 1990s. As a rule, I usually saw a photograph in a group exhibition or in some publication and then was so taken by it that I began to collect more extensive information on the artist. I remember that in Issei Suda’s case it was a picture of a snake winding its way up a wooden wall that immediately fascinated me, even if I was also somewhat perplexed by it.

RA: In the West, there is a tendency to associate Japanese postwar avant-garde photography only with names like Araki, Moriyama and – to a greater or lesser extent – the Provoke Group. Suda, as well as a few other important photographers, are, for the most part, only known to insiders. What do you think is the reason for this?

fb: It is a result of the way Japanese photography has been received in the West, it hasn’t progressed along a straight line in parallel with historical developments, it hasn’t been a case of first becoming familiar with the great masters and then branching to explore others. Instead, there was an initial tendency to concentrate on a very few photographers; hence, Nobuyoshi Araki was the first photographer to become well-known in the West, along with one of his contemporaries, Hiroshi Sugimoto, although the latter represents a completely different position. Nearly ten years later – in the wake of an exhibition that toured the world 1999 – the name Daidô Moriyama was added to this list. The focus in the cases of Moriyama and Araki was primarily on the Provoke era of the late the 1960s and early 1970s, while Sugimoto is still seen as a singular phenomenon to this day. Early on, there was little interest in how artists fit into a particular context in terms of the history of photography. This was, in part, a result of the fact that these artists fulfilled certain Western fantasies in relation to Japan. Araki stood, and still stands, for obsessive, excessive sexuality and its depiction. While the early work of Hiroshi Sugimoto, the Seascapes, were seen in connection with the philosophy and aesthetics of Zen Buddhism. The projection of Western fantasies onto the “Orient” is an essential aspect of the centuries’ old discourse on Orientalism. The West was always projecting images onto the Orient, particularly fantasies and topics considered taboo or unfulfilled in the West. While Araki clearly catered to some of these on a sexual level, Sugimoto – particularly in his early work – catered to completely different fantasies, namely those of a pre-industrial Japan, a land of geishas, Zen Buddhism and the tea ceremony. The West only began to take a notable interest in the history and underlying context of Japanese photography after we entered the new millennium. Issei Suda occupies a unique position in Japan, since he is not associated with any particular school. This is probably also the reason for his having received so much less attention than artists such as those in the Provoke Group, which formed around Daidô Moriyama, Nakahira Takuma and Yutaka Takanashi. His books are also not as well known in the West. Books by photographers are second only to photography exhibitions in terms of their importance for the reception of Japanese photography. Books by photographers are of much greater importance in Japan than in the West. In Japan, artists have traditionally presented their works to the public by means of their books and magazines and – as was previously mentioned – young artists are still more likely to have a publisher than a gallerist.

RA: Ferdinand, can you tell me, briefly, what role Issei Suda played in Japanese postwar photography and whether he had as much influence on his contemporaries and the following generation as the Provoke Group did?

fb: While Issei Suda’s position within Japanese photography is certainly an original one, he was not the only one taking photographs in this manner: with a medium format camera, precisely observing his subjects, producing prints of the highest quality, and painstakingly describing what he saw. We already discussed the fact that the Provoke Group was extremely influential – within and, especially, beyond Japan. Shortly before the Provoke Movement was established in the late 1960s, another group was founded under the name “Kompora”, and it can be seen as the diametric opposite of Provoke. The term “Kompora” is a typically Japanese composite created from English words; it was a combination of the Western terms “contemporary” and “photography”. The term was derived from the title of the exhibition Contemporary Photography: Towards a Social Landscape at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York. Both movements, “Provoke” and “Kompora” were formed as a means of countering journalistic photography, which was predominant at the time and which they charged with encountering reality through its ideological preconceptions. While the Provoke Group’s grasp of reality extremely radicalized photography by refusing to adhere to a traditional visual grammar; instead they held the camera at an angle, caused blurring, captured hard contrasts and grainy shots, while the Kompura Group pursued the opposite path by saying, “We must divorce ourselves from all ideology and approach reality in a coolly objective and unemotional manner, working as precisely as possible, while concentrating on common, everyday images and events.” One does not, however, find this form of cool description in Issei Suda’s work. Although he develops each of his shots with incredible precision, his images also always describe reality with some form of subtle distortion. His works operate in a highly charged space somewhere between the objective depiction of everyday occurrences and often quite unusual views of everyday life that seem to embody some sense of mystery.

RA: In your view, is there a certain group of works that you would single out, or is there a particular series within his oeuvre of forty years that you would highlight?

fb: Generally, the quality of his work is impressively consistent. Nevertheless, I would highlight the series called Fûshi kaden, which he published in 1978. Fûshi kaden is a discourse on tradition and modernity – and this was conducted with particular intensity in Japan – and some artists were, on the one hand, interested in the modern metropolis, particularly Tôkyô, while others were simultaneously moving back to rural areas and concentrating on the old Japan, which was in a state of decline. It was mainly Japanese photographers who depicted this contrast, the radical tension between the burgeoning hypermodernity of major cities and the often still very traditional life in rural areas. Suda traveled through rural areas for Fûshi kaden and many of his photographs were of traditional festivals – called matsuri. The title, Fûshi Kaden, is difficult to translate. It is a reference to a book from the early fifteenth century, a theoretical treatise on Nô theater, written by one of the most important figures in Nô, the Grand Master Zeami. As a rule, Fûshi Kaden is translated as “transmission of the flower in acting style.” This translation does not really provide much help, because the translation includes the central concept of the “flower” derived from Zeami’s theory of Nô theater, which seems rather foreign to us: Zeami tells us that the flower is a symbol of beauty, whereby in Zeami’s view, the ideal of beauty – the “flower” – can be found in 7- to 8-year-old children who, because they have not yet fully blossomed, embody the greatest beauty. On the other hand, the term “flower” refers to a manner of acting in Nô theater. Zeami called upon actors to intensely combine their innermost feelings with the most precise perception of their surroundings, yet to never reveal everything in their acting, thereby retaining a secret of their own. Issei Suda seems to have applied this connection between the inner and the outer, between self-perception and the perception of one’s surroundings, as well as Zeami’s idea of beauty, to his photography. A recurrent theme in Suda’s work are young people, particularly young girls, often photographed in traditional clothing, in the summer kimonos that are worn to festivals. One gets the impression that he is not interested in providing a description of the people in his photography, but that he instead turns them into actors in a play, about which they know nothing. Ultimately, it is the theater of everyday life that serves as a model for Issei Suda’s precise and, at the same time, mysterious images. Another important aspect in this series is Suda’s eye for the beauty of graphic patterns, structures that he discovers along the way, whether in the pattern of a curtain or of some piece of clothing worn by his actors.

RA: Is it correct to say that Suda succeeds – despite the strong influence of Japanese history and tradition on his perceptions and his choice of motifs – in creating a modern image of Japan, albeit one that is more classic than provocative, as in the case of the Provoke Group?

fb: In Suda’s case, we see things coinciding, and this is always an essential factor in making Japanese art so unique: the fact that the Japanese draw from different sources. I already mentioned this in relation to the topics chosen by Japanese photographers in the 1960s and 1970s: the tense relationship between tradition and modernity: this is also a conflict in the life and work of artists from this period, and it is most radically reflected in the life of the author Yukio Mishima, who, as a representative of the avant-garde, took his own life through «sepukku», the traditional form of suicide, in 1970. Before he became a freelance photographer, Issei Suda was a theater photographer working for Shûji Terayama’s “Tenjô Sajiki” acting troupe. Terayama was one of the central figures in the Japanese avant-garde of the 1960s and had contact to a wide variety of artists from this period. Terayama worked with Tadanori Yoko’o, for example, one of the most important graphic designers in Japan (and he in turn worked with the photographer Eikô Hoso’e). There are also a number of early photographs of Daidô Moriyama taken within the context of this theatre troupe. Hence, there was an extremely lively and intensive network within the Japanese avant-garde that served to connect all of the arts during this period. Returning to the confrontation between tradition and modernity in Issei Suda’s work: after the period he spent as a theater photographer, it was not surprising that his first book drew its title from a work on the theory of acting. Yet it is also important to note that he chose a title from the Japanese Middle Ages, the title of a book by one of the founders of the Japanese theater tradition. His choice of this title is a reference to the fact that Issei Suda apparently sees reality with two different eyes. He bears witness to the changes in Japan, to its having been propelled into modernity, yet refers to an aesthetic style that is centuries old; and in doing so, he makes use of a visual medium that was, in turn, introduced to Japan from the West. This, in my opinion, is what is so special about Suda: this tension between the ordinary and the extraordinary, between tradition and modernity. This precise observation and description, whereby the unusual tension in these images, which always embody a sense of mystery, is what makes the work that Suda was doing so different from that of other artists in this period. The Provoke photographers, whose best works hit the viewer like a slap in the face, fail to demonstrate this subtlety.

RA: Was Suda integrated into the Japanese photography scene? And when was he first noticed by Japanese museums?

fb: In general, there has always been a very strong network within the photography scene in Japan. Personal contacts, magazines and exhibitions always provided a basis for a very close-knit network. One reason for this was that in the early decades photographic artists received very little support from outside of the photography scene; moreover, up until a few years ago, there was not much of a market for photography, nor were photographs discussed in magazines or newspapers outside of the photography scene. People tended to work for themselves and their colleagues within the scene, and to provide support for each other in realizing projects and staging exhibitions. Yet, in his work, Suda really seems to be original; he also denies having been influenced by others, although he was certainly, albeit unconsciously, affected by the “Kompora” movement, particularly since an intense discourse regarding the medium of photography was being conducted in the 1960s and 1970s, mainly in photography magazines and books by photographers. Unlike the Provoke artists, Suda did not establish a trend in photography, although his manner of seeing sometimes seems to shine through in the work of other photographers. Regarding Suda’s presentation in Japanese museums, I was surprised to realize that he has never had a solo exhibition in a Japanese museum, although his works can be found in many Japanese museum collections. Moreover, his work was first exhibited at Western institutions, such as the ICP in New York and the Forum Stadtpark in Graz. This is, on the one hand, due to historical reasons. Japanese museums did not establish photographic collections until the late 1980s or early 1990s. On the other hand, Japanese museums are very cautious about presenting Japanese artists. Quite often, Japanese artists are only appropriately recognized after they have had successful solo exhibitions in Western museums. Kusama Yayoi, the important Pop-Art artist, and Nobuyoshi Araki, as well as the current case of Rinko Kawauchi, are examples of this.

RA: Is it true that you, as the director of the Galerie Priska Pasquer, were responsible for introducing Suda in the West?

fb: I believe that the presentation of his work in our gallery marked an important step in acquainting Western collectors and curators with Issei Suda.

RA: Has Suda’s work been represented in the very few group exhibitions on Japanese photography staged in recent decades?

fb: Issei Suda’s work was shown in the important exhibition The History of Japanese Photography in Houston, Texas, in 2003. The catalogue from the exhibition can now be used as a reference work on the history of Japanese photography. It made an essential contribution to our knowledge of Japanese photography, particularly due to its in-depth research. Issei Suda’s work was also presented in earlier exhibitions. We have now largely forgotten that Japanese photography was already shown in the 1970s. There were three important exhibitions: New Japanese Photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, organized by John Szarkowski in 1974; Japan: A Selfportrait at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York in 1978 – in which Suda also participated; and Neue Japanische Fotografie in Graz, in 1977. They seem to have had little effect back then. They were, unjustifiably, not recognized in the West as extraordinary moments in exhibition history.

RA: As you correctly pointed out, Suda engaged with Japanese history – particularly with Nô theater. How do you assess his decision to turn to images of modern urban Japan, particularly to Street Photography, within the context of his overall oeuvre?

fb: Along with Fûshi kaden, I see the book Human Memory, which was created during the 1980s, as an important milestone in his work. In it you can really see a change taking place, Suda has returned to the city. He photographs everyday scenes – but not necessarily scenes from the vibrant centre of the metropolis of Tôkyô, he instead shows side streets and areas that seem more like small towns. While in Fûshi kaden Suda repeatedly showed people in groups, couples and cliques, or people celebrating, sometimes assuming exaggerated poses, one notices that many of his photographs in Human Memory depict a sense of isolation.There is still the strange tension in Suda’s images, which is based on the depiction of the unusual in everyday life – which seem, however, somehow muted. The focus is more on the scenes in which people appear as isolated individuals in an urban context.

RA: Does that mean that he is reacting to what was then a contemporary trend, one that was surely quite confusing for the more traditional and family-minded Japanese?

fb: He is indeed examining – consciously or unconsciously – a social trend that became quite pronounced in Japan in this period. The major cities – above all the Tôkyô metropolitan region, which is now inhabited by over 32 million people – exerted a tremendous attraction; people moved to the cities and were thus torn out of their village communities. In the cities, the people now appear as isolated individuals. Tôkyô’s rise, the rapid changes in the appearance of the city and the radical transformation of the social structure play a central role in the discourse in Japanese photography during this period.

RA: Ferdinand, I thank you for speaking with me.

This interview with Ferdinand Brüggemann was conducted by Roland Angst on October 11, 2011 at the Galerie Priska Pasquer in Cologne.

Ferdinand Brueggemann Photo historian and Director of Galerie Priska Pasquer in Cologne, where he is responsible for Japanese photography and, since 2001, solo exhibitions on Shômei Tômatsu, Eikô Hosoe, Ikkô Narahara, Daidô Moriyama, Issei Suda, Rinko Kawauchi, Asako Narahashi and others. He has worked in the Department of Photography at the Museum Folkwang in Essen, as a research intern at the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum in Duisburg, as a research fellow at the German Institute for Japanese Studies in Tôkyô, as a guest lecturer on Japanese art and photography at the University of Frankfurt, and as an author, lecturer and speaker on Japanese photography.