“When we first had the Daido Moriyama exhibition in 2004, nobody was interested,” recalls Cologne gallerist Priska Pasquer of the photographer whose most prized bodies of work from the 1960s and ’70s document the seedy streets of the Shinjuku district in Tokyo. “This changed completely in the past decade.”

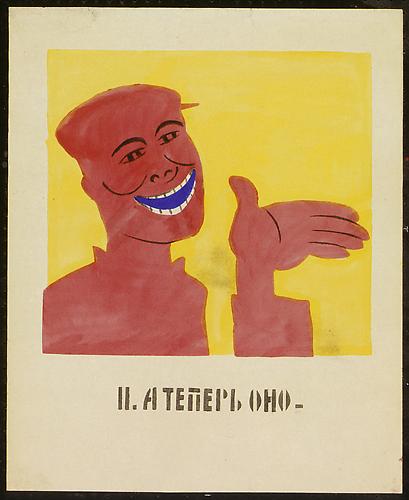

Moriyama is but one of several postwar Japanese photographers to be rediscovered by Western markets over the last 10 years. Among the others whom Pasquer herself promoted at Paris Photo in the 2000s are Eikoh Hosoe, whose first book, Killed by Roses, 1963, featured Yukio Mishima as model and muse in psychologically fraught erotic imagery; and Shomei Tomatsu, who collaborated with Ken Domon on the photo book Hiroshima–Nagasaki Document 1961, which explored the lingering effects of the atomic bombs. These three, together with Masahisa Fukase, Yutaka Takanashi, Takuma Nakahira, and Kikuji Kawada, rank among the top tier of photographers gaining recognition in Europe and America under the banner of the Provoke movement, named for a short-lived avant-garde magazine many were affiliated with. (Another key Provoke artist, Nobuyoshi Araki, was already familiar in the West, though principally for his later, sexually explicit works.) In the aftermath of World War II, these artists cast aside the dispassionate observations of the documentary tradition and embraced deeply subjective styles, producing images that are jittery and stark, and often expose erotic machinations.

Western collectors’ newfound curiosity about the Provoke artists follows a concerted campaign by a handful of players that demonstrates both how changing tastes alter markets, and how markets can change tastes.

That campaign’s success so far rests on a confluence of trends. By the turn of the century, dealers and auction houses had successfully established a canon of Western photographers, flushed out most troves of their vintage work, and driven prices for it beyond the reach of new collectors. Dealers set out to find new sources of affordable material, and several Europeans looked to Asia. At the same time, the once marginalized field of photography was becoming more entwined with contemporary art, and young collectors who came to the medium through the work of later American artists like Larry Clark and Nan Goldin were primed for the earlier Japanese photographers’ gritty aesthetic, which soon earned the label are, bure, boke (“rough, blurred, out-of-focus”). Dealers were not alone in rediscovering this work. A number of museum curators, eager to explore new material and attracted to these pieces’ affordability, mounted exhibitions that in turn amplified dealers’ efforts to attract and educate collectors.

While both vintage and new prints now claim prices undreamed of by the photographers 15 years ago, they remain relatively affordable. “We are seeing a unique window in which you can buy masterworks for under $10,000 to $20,000,” says London photo dealer Michael Hoppen, whose gallery deals with many of the photographers or their estates, including Fukase, Kawada, and Miyako Ishiuchi. “If you were to look at masterworks by American or European photographers—even late prints by OK photographers—they are going for much more than that.”

Art markets regularly stage rediscoveries of both individual artists and supposedly undervalued movements—witness the recent rise of Gutai. The Provoke story appears to be a success: Endangered works have been brought to light and preserved, institutional validation of their art historical worth has been established, and prices have increased at a measured pace. But before the full impact of the market-driven resurgence is understood, questions remain, ranging from issues of recontextualization to the balance of supply and demand.

The market growth in the West has not been matched in Japan. This may be chalked up to the relatively small size of the country’s photo collector base. Likely, however, the lack of a surge in Japan stems also from collectors there being more attuned to the photographers’ original intentions, which revolved almost exclusively around the creation of photo books.

…

Japan’s postwar innovators piqued the interest of American and European curators decades before the dealers took notice. In 1974, Domon and Kawada were among those recognized in the first survey outside the country, “New Japanese Photography,” curated by Yamagishi and John Szarkowski for the Museum of Modern Art in New York. More surveys followed in this first wave, at the Graz Municipal Art Museum in Austria in 1976 and ’77, at Bologna’s Museum of Modern Art in 1978, and at the International Center of Photography in New York in 1979.

…

The market, in turn, has played a role in driving the museum exposure through the Provoke material’s relative affordability. Tate Modern, for example, never collected photography before curator Simon Baker joined the institution in 2009, immediately facing the challenge of building the collection from scratch while staying within budget. The attractive price point of the Provoke-era photography as well as access to living photographers who were able to make available complete bodies of work—the museum’s preferred method of collecting—helped make the effort feasible. “We don’t collect things because they are cheaper,” says Baker. “But with the Tate starting its collection very late, there are some things we see that are not viable for a museum—that arguably should have been bought when they were at a reasonable value, or that we should wait for as donations. We really have to think about how we use the resources we have.” Having collected work from a range of Provoke photographers in short order, the museum has in recent years mounted two shows with heavy emphasis on the field: “William Klein+Daido Moriyama” in 2012 and “Conflict, Time, Photography” in 2014. A third, “Performing for the Camera,” opens in February 2016, with work by Hosoe and Fukase, among others.

…

October also saw the unveiling at New York’s Japan Society of “For a New World to Come: Experiments in Japanese Art and Photography, 1968–1979,” running through January 10 and featuring the work of Ishiuchi, Moriyama, Tomatsu, and Jiro Takamatsu. And in January 2016, the Albertina in Vienna will debut a show of Provoke photographs curated by Matthew Witkovsky; it moves to the organizing museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, in July.

…

The move by auction houses to capitalize on the current moment has not gone unnoticed by the dealers who toiled for years to build the market. “This is virgin market with no actual control yet, which is why I think all the big auction houses are jumping in,” says Hoppen. The dealer cautions that the rush to bring new material to light may attract those interested in the market potential more than the aesthetics. “I don’t think one should be under the illusion that this is going to be driven purely by taste.”

Despite Hoppen’s concerns, the early dealers themselves have played a role in pushing ever more material to market. Most Provoke photographers are now septuagenarians and octogenarians, but many still living continue to work. Once the vintage output inventory became more difficult to find, some dealers in Japan and the West also started working with the photographers to create modern prints of old work on demand. “There is a great demand for the vintage prints,” says Zurich dealer Guye. “However, collectors can also benefit from the availability of modern prints, as Moriyama’s most iconic images are still available, and modern prints hand-proofed by the artist become vintage prints over time.” Gallerist Pasquer insists that the cultural divide still persists, making modern prints issued in open editions an inevitability. “You cannot work with Japanese photographers with this Western idea of editions,” she says.

Full article at: Blouinartinfo